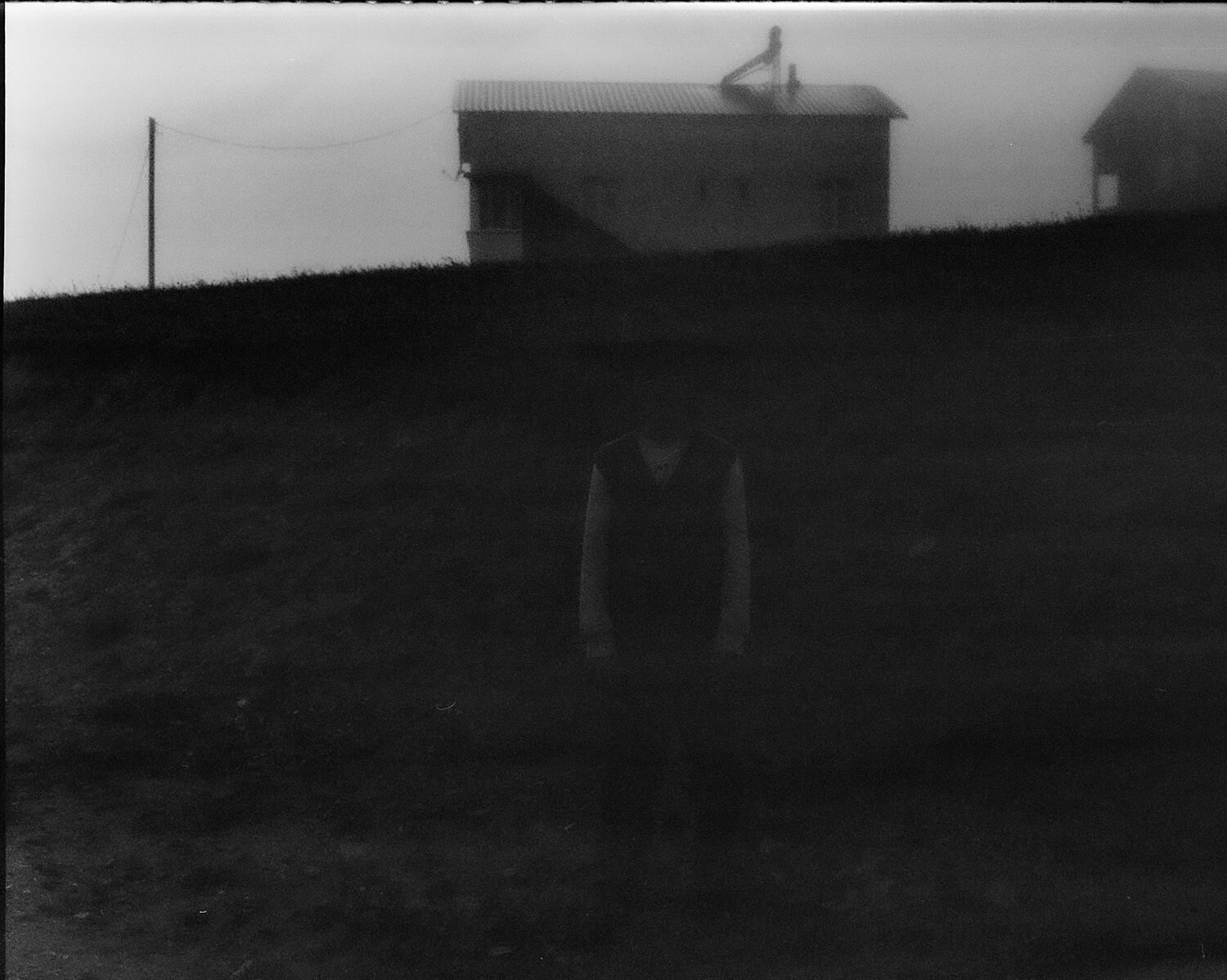

Deep in a valley of the Kuşmer Highlands, in the Black Sea region of Turkey, lies the village and ancestral my homeland: Çaykara. Tradition decrees that the women of this village may not own the homes or the land that they live in that right belongs to men, exclusively. I photographed this landscape, and the women who inhabit it, by way of a personal investigation into identity, belonging, and what it means when neither of those are certain.

Çaykara is a place with many layers of ‘roots’. In the first half of the 20th century, the mother tongue of most of the region’s residents was Pontic Greek, colloquially known as Romeyka; however, due to resettlement and government intervention, the use of the language has steadily declined, and is now largely kept alive by the village’s oldest generations. In the 1960s, all of the villages in the region were officially renamed, further encroaching upon the residents’ sense of identity.

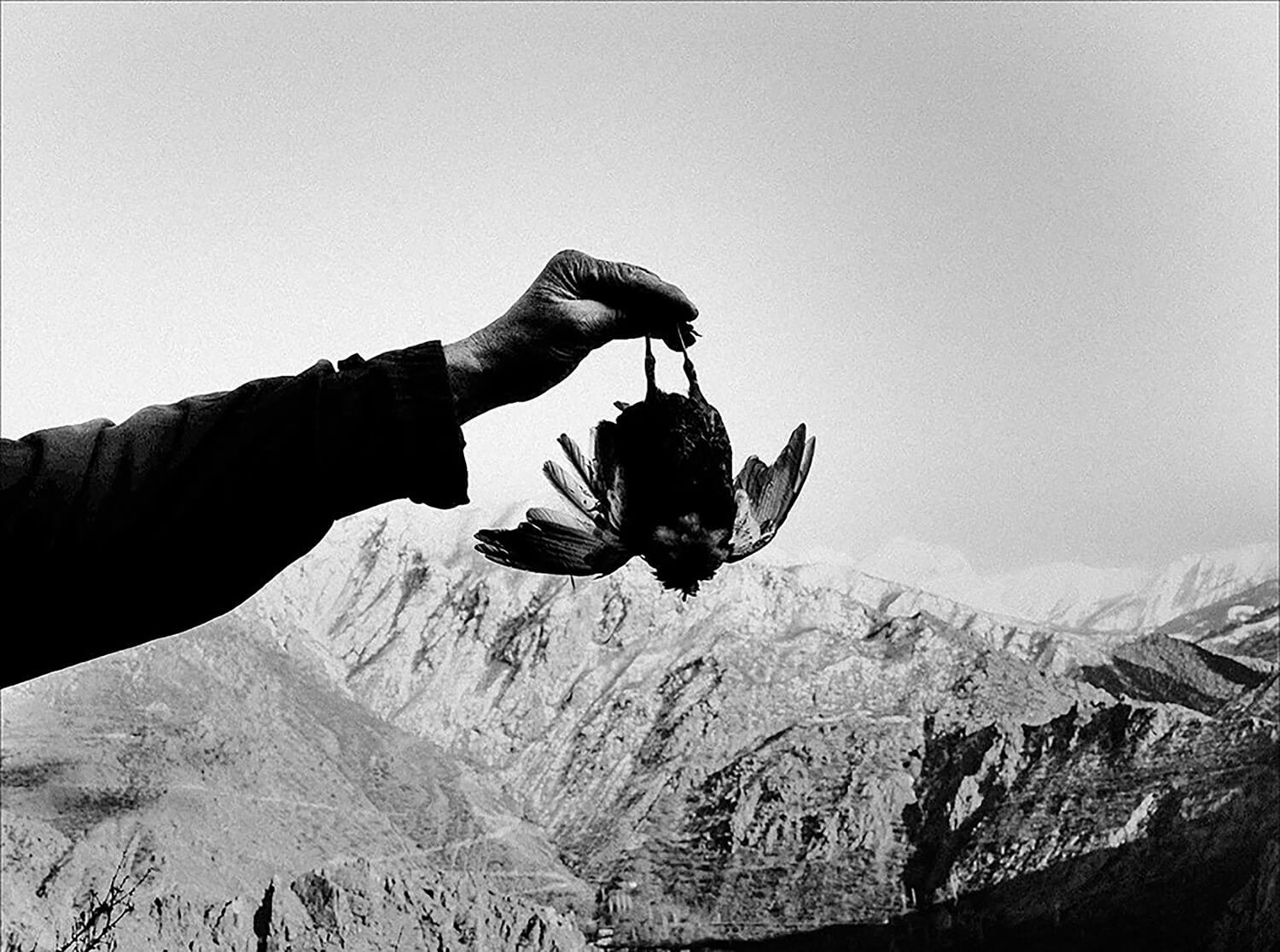

Many within the community of Çaykara still practice a life of transhumance, with much of their tradition and identity rooted in this way of life: they migrate seasonally with their cattle from settlement to settlement. But a growth in tourism over the years has led to further dispossession our way of life is slowly becoming commodified, and our once tranquil lands are now home to an increasing number of hotels and inns.I spent most of my childhood summers in Çaykara, although it was only as an adult that I came to understand why my mother, and all of the women of the village, could never feel a true sense of ownership for this land. The struggle between attaining identity and the tension between these two opposing forces has always been a point of contention for me. In photographing the women of my ancestral homeland, I form a renewed intimacy with my roots, reconciling the sense of dispossession that I came to understand as my escape.